Juzo Itami

Juzo Itami | |

|---|---|

伊丹 十三 | |

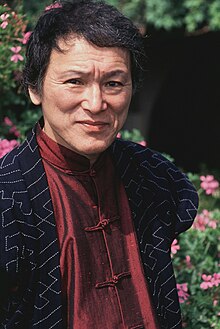

Itami in 1992 | |

| Born | Yoshihiro Ikeuchi (池内 義弘) May 15, 1933 Kyoto, Japan |

| Died | December 20, 1997 (aged 64) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, screenwriter, actor |

| Years active | 1960–1997 |

| Spouse(s) | Kazuko Kawakita (1960–66) Nobuko Miyamoto (1969–1997) |

| Father | Mansaku Itami |

| Relatives | Hikari Ōe (nephew) |

Juzo Itami (伊丹 十三, Itami Jūzō), born Yoshihiro Ikeuchi (池内 義弘, Ikeuchi Yoshihiro, May 15, 1933 – December 20, 1997), was a Japanese actor, screenwriter and film director. He directed eleven films (one short and ten features), all of which he wrote himself.

He is the namesake of the Juzo Itami Award, founded in 2009 to honor his legacy.

Early life

[edit]Itami was born Yoshihiro Ikeuchi in Kyoto.[1] The name Itami was passed on from his father, Mansaku Itami, a renowned satirist and film director before World War II. In his childhood, he went by the name Takehiko Ikeuchi (池内 岳彦).[2]

At the end of the war, when he was in Kyoto, Itami was chosen as a prodigy and educated at Tokubetsu Kagaku Gakkyū ("the special scientific education class") as a future scientist who was expected to defeat the Allied powers. Among his fellow students were the sons of Hideki Yukawa and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga. This class was abolished in March 1947.[citation needed]

He moved from Kyoto to Ehime Prefecture when he was a high school student. He attended the prestigious Matsuyama Higashi High School, where he was known for being able to read works by Arthur Rimbaud in French. Due to his poor academic record, he had to remain in the same class for two years; it was here that he became acquainted with Kenzaburō Ōe, who later married his sister.

When he was unable to graduate from Matsuyama Higashi High School, he transferred to Matsuyama Minami High School and graduated thereafter.[citation needed] After failing the entrance exam for the College of Engineering at Osaka University, Itami worked at times as a commercial designer and writer, illustrator, television reporter, and essayist.[3] He was also the editor-in-chief for the 1980s psychoanalytic magazine Mon Oncle.[4][5]

In his early acting days, Itami lived in London. By the time he became a director, he spoke English near-flawlessly, although preferred to use an interpreter during interviews.[6]

Itami was the brother-in-law of Kenzaburō Ōe and an uncle of Hikari Ōe.

Acting career

[edit]

Itami studied acting at an acting school called Butai Geijutsu Gakuin in Tokyo. In January 1960 he joined Daiei Film and was given the stage name Itami Ichizō (伊丹 一三) by Masaichi Nagata. In May 1960, Itami married Kazuko Kawakita, the daughter of film producer Nagamasa Kawakita. He first acted on screen in Ginza no Dora-Neko (1960). In 1961 he left Daiei and started to appear in foreign-language films such as 55 Days at Peking. In 1965 he appeared in the big-budget Anglo-American film Lord Jim. In 1965 he published a book of essays which became a hit, Yoroppa Taikutsu Nikki ("Diary of Boredom in Europe"). In 1966 he and Kazuko agreed to divorce.

In 1967, when working with director Nagisa Ōshima on the set of Sing a Song of Sex (Nihon Shunka Kō) he met Nobuko Miyamoto. He and Miyamoto married in 1969 and he became the stepfather to her two children.[7] Around this time, he changed his stage name to "伊丹 十三" (Itami Jūzō) with the kanji "十" (ten) rather than "一" (one), and with 十三 meaning "thirteen", and worked as a character actor in film and television.

In 1968 he played Saburo Ishihara, the father of Takeshi and Koji during the second season of the children's series Cometto-san. He became well known for this role in many Spanish-speaking countries, along with Yumiko Kokonoe who played the lead role.

In the 1970s, he joined the TV Man Union television production company and produced and presented documentaries for television, which influenced his later career as a film director. He also worked as a reporter for a TV program called Afternoon Show.

In 1983, Itami played the father in both Yoshimitsu Morita's The Family Game and in Kon Ichikawa's The Makioka Sisters, roles for which he won the Hochi Film Award and Best Supporting Actor at the Yokohama Film Festival.

Along with his acting career, he translated several English books into Japanese, including Papa, You're Crazy by William Saroyan, The Kitchen Sink Papers: My Life as a Househusband by Mike McGrady, and The Potato Book by Myrna Davis and Truman Capote.[8][9]

Director

[edit]Itami's debut as director was the movie The Funeral (Osōshiki) in 1984, at the age of 51. This film proved popular in Japan and won many awards, including Japanese Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay. However, it was his second movie, the 1985 "noodle western" Tampopo, that earned him international exposure and acclaim.[10]

His following film A Taxing Woman (1987) was again highly successful. It won six major Japanese Academy awards and spawned a sequel A Taxing Woman's Return in 1988. The central character, played by his wife Nobuko Miyamoto who appeared in all his films, became a pop culture heroine.[11] This was followed by his fifth film A-Ge-Man: Tales of a Golden Geisha.

Itami directed the anti-yakuza satire Minbo: the Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion as his sixth feature. On May 22, 1992, six days after the release of the film, Itami was attacked, beaten, and slashed on the face by five members of the Goto-gumi, a Shizuoka-based yakuza clan, who were angry at Itami's film's portrayal of gang members. In an interview with the New York Times, he described the attack, saying, "They cut very slowly; they took their time. They could have killed me if they wanted."[12] This attack led to a government crackdown on the yakuza.[12]

His subsequent stay in a hospital inspired his next film Daibyonin (1993), a grim satire on the Japanese health system.[13] During a showing of this film in Japan, a cinema screen was slashed by a right-wing protester.[14]

Before his death, he directed another three films: A Quiet Life (based on the Kenzaburō Ōe novel), Supermarket Woman, and Woman in Witness Protection.

Recurring cast members

[edit]Itami frequently re-cast actors whom he had worked with on previous films.

Actor Work

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Funeral | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tampopo | ||||||||||||||||||||

| A Taxing Woman | ||||||||||||||||||||

| A Taxing Woman's Return | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tales of a Golden Geisha | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Minbo | ||||||||||||||||||||

| The Last Dance | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Shizuka na Seikatsu | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Supermarket Woman | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Marutai no Onna |

Death

[edit]Itami died on December 20, 1997[15] in Tokyo after falling from the roof of the building where his office was located. On his desk was found a suicide note written on a word processor[16] stating that he had been falsely accused of an affair and was taking his life to clear his name. Two days later, a tabloid magazine published a report of such an affair.[17]

However, no one in Itami's family believed that he would have taken his life or that he would be mortally embarrassed by a real or alleged affair. In 2008, a former member of the Goto-gumi yakuza group told reporter Jake Adelstein: "We set it up to stage his murder as a suicide. We dragged him up to the rooftop and put a gun in his face. We gave him a choice: jump and you might live or stay and we'll blow your face off. He jumped. He didn't live."[18][19] The attack is thought to have been due to the topic of Itami's next film, which was rumored to have been focusing on connections between the Goto-gumi and the cult-like Soka Gakkai religious group.[20]

Tributes

[edit]His brother-in-law and childhood friend Kenzaburō Ōe wrote The Changeling (2000) based on their relationship.[21]

There is a Juzo Itami museum in Matsuyama. The memorial museum was designed by architect Yoshifumi Nakamura and contains a special exhibition, rotating its displays every 1–2 years, a permanent exhibition, divided up into thirteen sections to reflect the "thirteen" meaning of Itami's name, and an outdoor courtyard. It also houses a cafe named "Café Tampopo" after the film.[2][22]

Filmography

[edit]As an actor

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Ginza no dora-neko | ||

| 1961 | A False Student | Soratani (as Ichizō Itami) | |

| 1961 | Her Brother | Son of Factory Owner | Uncredited |

| 1961 | The Big Wave | Toru | |

| 1961 | Ten Dark Women | Hanamaki | |

| 1963 | Onna no tsuribashi | Saburô Ôki | (Episode 2) |

| 1963 | 55 Days at Peking | Col. Shiba | |

| 1964 | Shûen | Takuji Yoshii | |

| 1965 | Lord Jim | Waris | |

| 1966 | Otokonokao wa rirekisho | ||

| 1967 | Sing a Song of Sex | Ôtake | |

| 1967 | Choueki juhachi-nen: kari shutsugoku | ||

| 1968 | Shôwa genroku Tokyo 196X-nen | ||

| 1968 | Ah kaiten tokubetsu kogekitai | ||

| 1968 | Ah, yokaren | Miyamoto | |

| 1969 | Kinpeibai | Hsi Men Ching | |

| 1969 | Eiko e no 5,000 kiro | ||

| 1969 | Heat Wave Island | Iino | |

| 1970 | Hiko shonen: Wakamono no toride | Ishizaka | |

| 1971 | Yasashii Nippon jin | ||

| 1973 | Kunitori Monogatari | Ashikaga Yoshiaki | TV series |

| 1973 | Shinsho Taikōki | Araki Murashige | TV series |

| 1974 | Lady Snowblood: Love Song of Vengeance | Ransui Tokunaga | |

| 1974 | Imôto | Kazuo Wada | |

| 1974 | Waga michi | ||

| 1975 | Wagahai wa neko de aru | Meitei | |

| 1979 | Collections privées | (segment "Kusa-Meikyu") | |

| 1979 | No More Easy Life | Takamizawa - Landlord | |

| 1979 | Grass Labyrinth | Principal / Priest / Old man | Short |

| 1980 | Yūgure made | Sasa | |

| 1981 | Slow na boogie ni shitekure | Lawyer | |

| 1981 | Shikake-nin Baian | Sahei Oumiya | |

| 1981 | Akuryo-To | Ryuhei Ochi | |

| 1982 | Kiddonappu burûsu (Kidnap Blues) | ||

| 1983 | The Makioka Sisters | Tatsuo Makioka, Tsuruko's husband | |

| 1983 | The Family Game | Mr. Numata, the father | |

| 1983 | Meiso chizu | Itakura | |

| 1983 | Izakaya Chōji | Kawara | |

| 1984 | Make-up | Kumakura | |

| 1984 | MacArthur's Children (Setouchi shonen yakyu dan) | Hatano | |

| 1985 | The Excitement of the Do-Re-Mi-Fa Girl | Professor Hirayama | [23][dead link] |

| 1985 | Haru no Hatō | Itō Hirobumi | TV series |

| 1989 | Sweet Home | Yamamura | (final film role) |

As director

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Rubber Band Pistol | Short film |

| 1984 | The Funeral | |

| 1985 | Tampopo | |

| 1987 | A Taxing Woman | |

| 1988 | A Taxing Woman's Return | |

| 1990 | Tales of a Golden Geisha | |

| 1992 | Minbo | |

| 1993 | The Last Dance | |

| 1995 | Shizuka na Seikatsu | "A Quiet Life" |

| 1996 | Supermarket Woman | |

| 1997 | Marutai no Onna | "Woman in Witness Protection" |

Awards

[edit]- 1985 Japan Academy Prize for Director of the Year—The Funeral

- 1988 Japan Academy Prize for Director of the Year—A Taxing Woman

References

[edit]- ^ Kirkup, James (23 December 1997). "Obituary: Juzo Itami". The Independent.

- ^ a b "About the ITAMI JUZO MUSEUM". ITAMI JUZO MUSEUM. Archived from the original on 2023-06-08. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "DVD-『13の顔を持つ男-伊丹十三の肖像』". 伊丹十三記念館オンラインショップ (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2023-06-10. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "Juzo Itami: mon oncle Weeks Hardcover Book". Hobonichi Techo. Archived from the original on 2023-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "〝伊丹十三〟を知らなかったぼくの伊丹十三体験記 | 特集『伊丹十三』vol.6". ぼくのおじさん|おじさんの知恵袋マガジン|MON ONCLE (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2023-03-13. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (1989-06-18). "What's So Funny About Japan?". The New York Times. p. 26. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "記念館の展示・建物 → 企画展 「おじさんのススメ シェアの達人・伊丹十三から若い人たちへ」". ITAMI JUZO MUSEUM. Archived from the original on 2023-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "伊丹十三コーナー". Archived from the original on 2023-06-08. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "伊丹十三記念館 記念館便り 『ポテト・ブック』". ITAMI JUZO MUSEUM. 2014-06-23. Archived from the original on 2023-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Vincent Canby (March 26, 1987). "New Directors/New Films; 'Tampopo,' A Comedy from Japan". The New York Times.

- ^ Bornoff, Nick (4 May 1989). "The king of comedy". Far Eastern Economic Review. pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b The New York Times

- ^ Jameson, Sam (1993-05-31). "A Master at Mixing Comedy, Commentary : Movies: Director Juzo Itami has been thinking about death. The result: 'Daibyonin,' which lashes out against the priority that science has won over human beings in Japan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Man Slashes Movie Screen in Protest". Associated Press News. May 30, 1993. Archived from the original on Dec 29, 2018.

- ^ Crow, Jonathan. "Juzo Itami". AllMovie. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Adelstein, Jake (2010). Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan. New York: Vintage Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-307-47529-9. OCLC 500797270.

- ^ "Filmmaker's Notes Allege Magazine Slur". Chicago Tribune. 22 December 1997.

- ^ "Reposted: The High Price of Writing About Anti-Social Forces – and Those Who Pay. 猪狩先生を弔う日々 : Japan Subculture Research Center". www.japansubculture.com. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ^ Adelstein, Jake (2009). Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan (1st ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-307-37879-8.

- ^ Djabarov, Aidan (2017-06-07). "Juzo Itami vs. The Yakuza". Filmed in Ether. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Tayler, Christopher (June 12, 2010). "The Changeling by Kenzaburo Oe". The Guardian.

- ^ Jones, Connie (2016-09-22). "See "Itami Juzo Museum" as architecture". Triplisher Stories. Archived from the original on 2023-06-16. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Fandango.com[full citation needed]

External links

[edit]- Juzo Itami at IMDb

- Juzo Itami at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)

- Juzo Itami's grave

- Itami Juzo Museum (in Japanese)

- Juzo Itami at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1933 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century Japanese male actors

- Critics of Sōka Gakkai

- Male actors from Kyoto

- Japan Academy Prize for Director of the Year winners

- Japanese film directors

- Japanese male film actors

- Japanese male television actors

- Japanese satirists

- Suicides by jumping in Japan

- Yakuza film directors

- 1997 suicides